The chapters of our life are often told in years, and the beginning of each one feels ripe with possibility—a clean slate, a fresh start, to move forward and build on the past, or forget it entirely. Historically, civilizations marked the first day of the year in accordance with either agricultural or astronomical occurrences, like times of harvest and moon phases.

For those of us who begin the year on January 1st, we have Julius Caesar to thank. In 46 BC, the emperor took it upon himself to solve problems with the early Roman calendar, namely that it had fallen out of sync with the sun. Together with the eminent astronomers and mathematicians of the time, he created a new calendar—one that begins in January, having taken inspiration from the Roman god of beginnings and transitions, Janus.

For many, this time has evolved into saying sayonara to the year with a party on December 31st and beginning anew, lists full of resolutions, on January 1st. It’s the version we see most often on screen, complete with sequins, champagne, and midnight kisses; but it’s certainly not the case for everyone. Across the globe, different countries, cultures, and religions celebrate their own New Years at different times, ritualizing what’s important to them and honouring ancient traditions.

Lunar New Year (China)

Chinese New Year, also known as the Lunar New Year or Spring Festival, is a 15-day long celebration that begins with the new moon between January 21st and February 20th, and ends with the full moon. This time is characterized with the colour red, which symbolizes luck, joy, and happiness—and can often be found on envelopes filled with money gifted to young people.

Every Chinese New Year begins with a different zodiac animal whose unique characteristics inform the year’s luck. The year 2021, for example, will be the year of the Ox, the zodiac animal known for its honesty, hard work, strength, and dependability.

Nowruz (Iran)

Also known as Persian New Year, Nowruz is hailed every year around the vernal equinox in March. Leading up to Nowruz, it’s common for families to assemble a collection of symbolic items all beginning with the letter S, called a haft-seen, or haft-sin. While the items may vary from family to family, haft-seen mainstays include:

Sabzeh: wheatgrass or sprouts to symbolize renewal

Senjed: dried fruit for love

Seeb: apple for beauty and health

Seer: garlic for healing

Samanu: sweet pudding for wealth and fertility

Serkeh: Persian vinegar for patience and wisdom

Somaq: also known as sumac, a red Persian spice representing the sunrise of a new day

Another important item that can often be found in this display is a “book of wisdom” like the Quran or Avesta. Elders in the family will sometimes select a passage in the book to offer insight for their family in the year ahead.

Hobiyee (Canada)

Hobiyee is a time in February recognized by the Nisga’a, Indigenous Peoples who are the original inhabitants of British Columbia’s northwest coast. Hobiyee centres on the last crescent moon of the winter, and the date varies depending on when this occurs. The name comes from the word for their traditional wooden spoon, the Hoobix, whose bowl-shape resembles the curve of the crescent moon.

The Nisga’a rely on the waxing moon, along with the stars, to indicate the abundance of food in the coming year. It’s said that if the moon’s crescent is open, plenty of salmon will be returning and berries will be plenty; if it’s closed, food may be more scarce. Hobiyee also symbolizes the return of eulachon (also referred to as “oolican”), a species of smelt that tends to arrive right when the winter food stores are dwindling.

Awal Muharram (Islamic New Year)

The Islamic lunar calendar has 12 months but only 354 days. Muharram, the first month of their calendar year, is also considered the most sacred among Muslims and has been celebrated ever since the prophet Mohammed fled Mecca to escape persecution on the same day in 622 AD.

How this time is celebrated varies among Islamic denominations (Shia and Sunni), but it is commonly a quiet time involving religious activities. It is also considered an important time to inwardly reflect on not just the passing of calendar days, but also the limited number of days in one’s own life.

Seollal (Korean New Year)

In Korea, the new year is celebrated on the first day of the Korean lunar calendar—in 2021, this will be on February 12th. Festivities typically last for three days, during which it’s common for families to gather, play games, share meals, and, most importantly, pay respect to elders and family members that have passed. Children often take part in Sebae, a ritual in which they show respect to their elders and wish them a happy new year with a deep bow. It’s common for elders to reward this act with gifts of money.

We Tripantu (Chile)

For the Indigenous Peoples of Chile, the new year follows their ancestral calendar, beginning with the winter solstice toward the end of June, and is steeped in gratitude for what the earth provides. Of Chile’s different Indigenous groups, the new year tradition of the Maphuche People—called We Tripantu, referring to the sun’s return—is most well known.

In addition to eating, drinking, dancing, and playing games, they will bathe themselves in a local river to wash away anything negative they’ve been carrying the past year. It’s a purifying ritual that allows them to begin the new year with a fresh start, and is often followed by prayer.

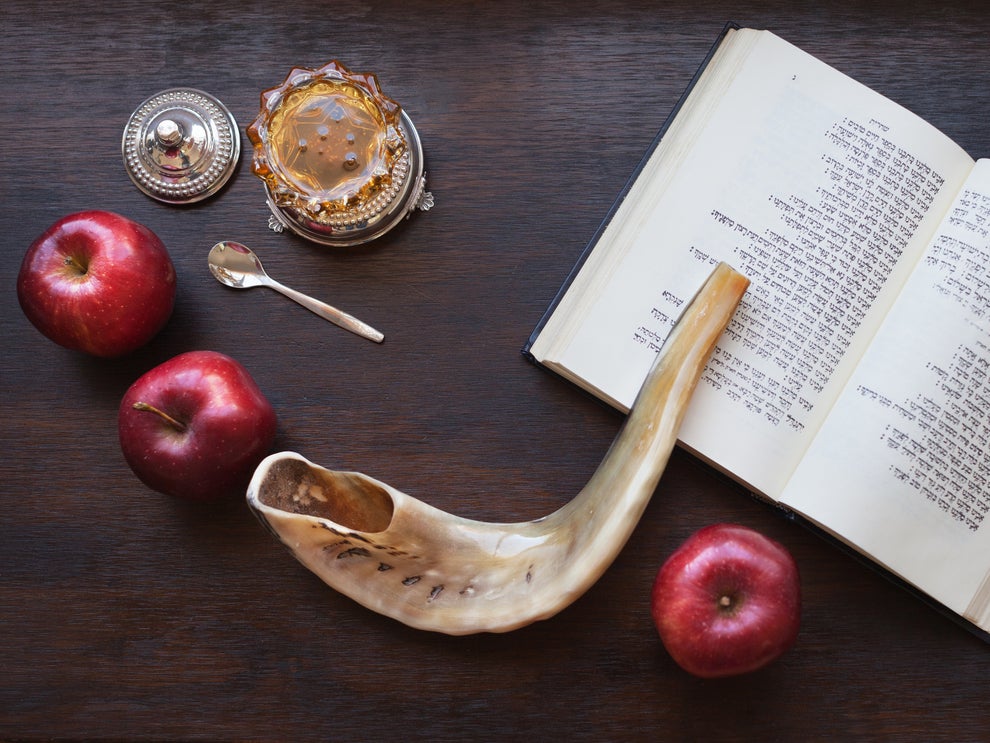

Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year)

Rosh Hashanah, which falls on the seventh month in the Hebrew calendar, celebrates not just a new year, but the birth of the universe. In contrast to North American new years celebrations, Rosh Hashanah is a subdued and introspective time lasting two days. In order to fully immerse oneself, those who celebrate Rosh Hashanah don’t go to work, and those who are religious will frequent synagogue. A sacred item in Rosh Hashanah is the shofar, a trumpet made from a ram’s twisted horn, that is sounded on both days of the holiday.